84 LAB: Cross Validation in Action

Note: This lab is in beta testing…

Don’t Judge the Ship After It Sinks

In 1912, the RMS Titanic sank on its maiden voyage, killing over 1,500 of the roughly 2,200 people on board. The disaster sent shockwaves through the maritime insurance industry. Lloyd’s of London, the world’s oldest and most famous insurance market, had underwritten a significant portion of the Titanic’s hull and cargo. The claims that followed forced insurers to confront an uncomfortable question: could the risk have been quantified in advance?

We’ve been hired by Lloyd’s to help answer a version of that question retrospectively. Using passenger records, we will build classification models that predict survival and then evaluate how trustworthy those predictions really are. Along the way, you will discover a fundamental problem in predictive modeling: a model that looks good on data it has already seen may perform poorly on data it has not. Cross validation is a classic remedy, and this lab will teach you why it works and how to implement it.

Learning goals

- Fit and interpret logistic regression classifiers for binary outcomes in R.

- Compute predicted probabilities, convert them into class predictions, and calculate accuracy.

- Explain why apparent (in-sample) accuracy is optimistic.

- Evaluate models using held-out data and implement k-fold cross validation.

- Reason about how the choice of probability cutoff affects classification decisions.

- Handle missing data responsibly and avoid information leakage in evaluation pipelines.

Getting started and warming up

Go to the course GitHub organization and locate the lab repo, which should be named something like lab-11-cross-validation. Either Fork it or use the template. Then clone it in RStudio. First, open the R Markdown document lab-11.Rmd and Knit it. Make sure it compiles without errors.

The data

We will work with two Titanic datasets that complement each other:

titanic_trainandtitanic_testfrom thetitanicpackage (a convenient train/test split often used in Kaggle contexts). The training set includes 891 passengers with known survival outcomes; the test set has 418 passengers.titanic3loaded from data/titanic3.xls, which includes additional fields such asboat(lifeboat number),body(body identification number), andhome.dest(home/destination). This version contains 1,309 passengers total. Originally from here.

We will have to combine these datasets at some point, but for now we will keep them separate to illustrate the difference between training and test data.

titanic3 <- read_excel("data/titanic3.xls",

col_types = c("numeric", "numeric", "text",

"text", "numeric", "numeric", "numeric",

"text", "numeric", "text", "text",

"text", "text", "text"))

data("titanic_train")

data("titanic_test")Each observation in these datasets represents a single passenger. Here are the key variables:

pclass: Passenger class (1 = 1st, 2 = 2nd, 3 = 3rd) — a proxy for socioeconomic statussurvived: Whether the passenger survived (1 = yes, 0 = no)name: Passenger name (includes title, e.g., Mr., Mrs., Dr.)sex: Passenger sex (male, female)age: Passenger age in years (fractional for children under 1)sibsp: Number of siblings/spouses aboardparch: Number of parents/children aboardticket: Ticket numberfare: Passenger fare in British poundscabin: Cabin number (many missing)embarked: Port of embarkation (C = Cherbourg, Q = Queenstown, S = Southampton)boat: Lifeboat number (if survived)body: Body identification number (if did not survive and body was recovered)home.dest: Home/destination

Before modeling, we will do two small cleanups: standardize column names to lowercase for titanic_test and titanic_train as well as create an ordinal level variable for passenger class. These are small steps, but they help keep the analysis tidy and reproducible.

# Rename columns to lowercase

names(titanic3) <- names(titanic3) %>% tolower()

names(titanic_train) <- names(titanic_train) %>% tolower()

names(titanic_test) <- names(titanic_test) %>% tolower()

# Convert pclass to factor

titanic_train <- titanic_train %>%

mutate(pclass_ord = factor(pclass, ordered = TRUE, levels = c(3, 2, 1)))

titanic_test <- titanic_test %>%

mutate(pclass_ord = factor(pclass, ordered = TRUE, levels = c(3, 2, 1)))

titanic3 <- titanic3 %>%

mutate(pclass_ord = factor(pclass, ordered = TRUE, levels = c(3, 2, 1)))Take a moment to explore the data. What variables are available? How many observations are in each dataset? Are there any missing values? Getting familiar with your data before modeling is always a good habit.

Exercises

Part 1: Apparent accuracy

Before we talk about cross validation, we need to see the problem it is designed to fix.

Suppose we fit a model and then immediately ask: “How well does this model predict the data?” If we use the same data to fit the model and to evaluate it, we are letting the model see the answers ahead of time. This is like a student who studies with the answer key and then takes the same test — of course the score looks good, but it tells us nothing about whether the student actually learned the material.

Let’s do that on purpose and see what happens.

Exercise 1: Fitting a model on full data

1.1. Fit a logistic regression predicting survival from passenger sex and class (as a numeric variable). Save the model as m_apparent.

Starter code

Click for a hint

#>

#> Call:

#> glm(formula = survived ~ sex + pclass, family = binomial, data = titanic3)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) 2.963 0.235 12.6 <2e-16

#> sexmale -2.515 0.147 -17.1 <2e-16

#> pclass -0.860 0.085 -10.1 <2e-16

#>

#> (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

#>

#> Null deviance: 1741.0 on 1308 degrees of freedom

#> Residual deviance: 1257.2 on 1306 degrees of freedom

#> AIC: 1263

#>

#> Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4Click for a solution

m_apparent <- glm(

survived ~ sex + pclass,

data = titanic3,

family = binomial

)

summary(m_apparent)

#>

#> Call:

#> glm(formula = survived ~ sex + pclass, family = binomial, data = titanic3)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) 2.963 0.235 12.6 <2e-16

#> sexmale -2.515 0.147 -17.1 <2e-16

#> pclass -0.860 0.085 -10.1 <2e-16

#>

#> (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

#>

#> Null deviance: 1741.0 on 1308 degrees of freedom

#> Residual deviance: 1257.2 on 1306 degrees of freedom

#> AIC: 1263

#>

#> Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4This model has access to every passenger and their final outcome. It is not being asked to predict the future. It is being asked to summarize the past. The coefficients tell us how survival odds differ by sex and class, but they don’t tell us how well the model would predict survival for new passengers.

1.2 Generate predictions

Now we can use the model to generate predicted survival probabilities for every passenger.

Click for a hint

#> 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

#> 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40

#> 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32

#> 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40

#> 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48

#> 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40

#> 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64

#> 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89

#> 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80

#> 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89

#> 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96

#> 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112

#> 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128

#> 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144

#> 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40

#> 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160

#> 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176

#> 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40

#> 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192

#> 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40

#> 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208

#> 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224

#> 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40

#> 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240

#> 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40

#> 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256

#> 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89

#> 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272

#> 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40

#> 273 274 275 276 277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288

#> 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40

#> 289 290 291 292 293 294 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304

#> 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40

#> 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320

#> 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336

#> 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22

#> 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22

#> 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368

#> 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22

#> 369 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384

#> 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22

#> 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400

#> 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22

#> 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416

#> 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78

#> 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432

#> 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22

#> 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448

#> 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22

#> 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22

#> 465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78

#> 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490 491 492 493 494 495 496

#> 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22

#> 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504 505 506 507 508 509 510 511 512

#> 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22

#> 513 514 515 516 517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525 526 527 528

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22

#> 529 530 531 532 533 534 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 542 543 544

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22

#> 545 546 547 548 549 550 551 552 553 554 555 556 557 558 559 560

#> 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78

#> 561 562 563 564 565 566 567 568 569 570 571 572 573 574 575 576

#> 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78

#> 577 578 579 580 581 582 583 584 585 586 587 588 589 590 591 592

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.78

#> 593 594 595 596 597 598 599 600 601 602 603 604 605 606 607 608

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 609 610 611 612 613 614 615 616 617 618 619 620 621 622 623 624

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59

#> 625 626 627 628 629 630 631 632 633 634 635 636 637 638 639 640

#> 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 641 642 643 644 645 646 647 648 649 650 651 652 653 654 655 656

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 657 658 659 660 661 662 663 664 665 666 667 668 669 670 671 672

#> 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 673 674 675 676 677 678 679 680 681 682 683 684 685 686 687 688

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59

#> 689 690 691 692 693 694 695 696 697 698 699 700 701 702 703 704

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11

#> 705 706 707 708 709 710 711 712 713 714 715 716 717 718 719 720

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 721 722 723 724 725 726 727 728 729 730 731 732 733 734 735 736

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 737 738 739 740 741 742 743 744 745 746 747 748 749 750 751 752

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 753 754 755 756 757 758 759 760 761 762 763 764 765 766 767 768

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 769 770 771 772 773 774 775 776 777 778 779 780 781 782 783 784

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 785 786 787 788 789 790 791 792 793 794 795 796 797 798 799 800

#> 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 801 802 803 804 805 806 807 808 809 810 811 812 813 814 815 816

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 817 818 819 820 821 822 823 824 825 826 827 828 829 830 831 832

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 833 834 835 836 837 838 839 840 841 842 843 844 845 846 847 848

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 849 850 851 852 853 854 855 856 857 858 859 860 861 862 863 864

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11

#> 865 866 867 868 869 870 871 872 873 874 875 876 877 878 879 880

#> 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11

#> 881 882 883 884 885 886 887 888 889 890 891 892 893 894 895 896

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 897 898 899 900 901 902 903 904 905 906 907 908 909 910 911 912

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 913 914 915 916 917 918 919 920 921 922 923 924 925 926 927 928

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 929 930 931 932 933 934 935 936 937 938 939 940 941 942 943 944

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 945 946 947 948 949 950 951 952 953 954 955 956 957 958 959 960

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11

#> 961 962 963 964 965 966 967 968 969 970 971 972 973 974 975 976

#> 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 977 978 979 980 981 982 983 984 985 986 987 988 989 990 991 992

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 993 994 995 996 997 998 999 1000 1001 1002 1003 1004 1005 1006 1007 1008

#> 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59

#> 1009 1010 1011 1012 1013 1014 1015 1016 1017 1018 1019 1020 1021 1022 1023 1024

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 1025 1026 1027 1028 1029 1030 1031 1032 1033 1034 1035 1036 1037 1038 1039 1040

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59

#> 1041 1042 1043 1044 1045 1046 1047 1048 1049 1050 1051 1052 1053 1054 1055 1056

#> 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11

#> 1057 1058 1059 1060 1061 1062 1063 1064 1065 1066 1067 1068 1069 1070 1071 1072

#> 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 1073 1074 1075 1076 1077 1078 1079 1080 1081 1082 1083 1084 1085 1086 1087 1088

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11

#> 1089 1090 1091 1092 1093 1094 1095 1096 1097 1098 1099 1100 1101 1102 1103 1104

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1105 1106 1107 1108 1109 1110 1111 1112 1113 1114 1115 1116 1117 1118 1119 1120

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1121 1122 1123 1124 1125 1126 1127 1128 1129 1130 1131 1132 1133 1134 1135 1136

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1137 1138 1139 1140 1141 1142 1143 1144 1145 1146 1147 1148 1149 1150 1151 1152

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59

#> 1153 1154 1155 1156 1157 1158 1159 1160 1161 1162 1163 1164 1165 1166 1167 1168

#> 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1169 1170 1171 1172 1173 1174 1175 1176 1177 1178 1179 1180 1181 1182 1183 1184

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11

#> 1185 1186 1187 1188 1189 1190 1191 1192 1193 1194 1195 1196 1197 1198 1199 1200

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11

#> 1201 1202 1203 1204 1205 1206 1207 1208 1209 1210 1211 1212 1213 1214 1215 1216

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1217 1218 1219 1220 1221 1222 1223 1224 1225 1226 1227 1228 1229 1230 1231 1232

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59

#> 1233 1234 1235 1236 1237 1238 1239 1240 1241 1242 1243 1244 1245 1246 1247 1248

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 1249 1250 1251 1252 1253 1254 1255 1256 1257 1258 1259 1260 1261 1262 1263 1264

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 1265 1266 1267 1268 1269 1270 1271 1272 1273 1274 1275 1276 1277 1278 1279 1280

#> 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 1281 1282 1283 1284 1285 1286 1287 1288 1289 1290 1291 1292 1293 1294 1295 1296

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1297 1298 1299 1300 1301 1302 1303 1304 1305 1306 1307 1308 1309

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11Click for a solution

p_apparent <- predict(m_apparent, type = "response")

p_apparent

#> 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

#> 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40

#> 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32

#> 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40

#> 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48

#> 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40

#> 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64

#> 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89

#> 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80

#> 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89

#> 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96

#> 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112

#> 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128

#> 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144

#> 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40

#> 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160

#> 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176

#> 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40

#> 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192

#> 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40

#> 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208

#> 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224

#> 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40

#> 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240

#> 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40

#> 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256

#> 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89

#> 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272

#> 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40

#> 273 274 275 276 277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288

#> 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40

#> 289 290 291 292 293 294 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304

#> 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.40

#> 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320

#> 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.89 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.89

#> 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336

#> 0.40 0.40 0.89 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22

#> 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22

#> 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368

#> 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22

#> 369 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384

#> 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22

#> 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400

#> 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22

#> 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416

#> 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78

#> 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432

#> 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22

#> 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448

#> 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22

#> 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22

#> 465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78

#> 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490 491 492 493 494 495 496

#> 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22

#> 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504 505 506 507 508 509 510 511 512

#> 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22

#> 513 514 515 516 517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525 526 527 528

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22

#> 529 530 531 532 533 534 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 542 543 544

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22

#> 545 546 547 548 549 550 551 552 553 554 555 556 557 558 559 560

#> 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78

#> 561 562 563 564 565 566 567 568 569 570 571 572 573 574 575 576

#> 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78

#> 577 578 579 580 581 582 583 584 585 586 587 588 589 590 591 592

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.78 0.78

#> 593 594 595 596 597 598 599 600 601 602 603 604 605 606 607 608

#> 0.22 0.78 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.78 0.78 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 609 610 611 612 613 614 615 616 617 618 619 620 621 622 623 624

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59

#> 625 626 627 628 629 630 631 632 633 634 635 636 637 638 639 640

#> 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 641 642 643 644 645 646 647 648 649 650 651 652 653 654 655 656

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 657 658 659 660 661 662 663 664 665 666 667 668 669 670 671 672

#> 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 673 674 675 676 677 678 679 680 681 682 683 684 685 686 687 688

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59

#> 689 690 691 692 693 694 695 696 697 698 699 700 701 702 703 704

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11

#> 705 706 707 708 709 710 711 712 713 714 715 716 717 718 719 720

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 721 722 723 724 725 726 727 728 729 730 731 732 733 734 735 736

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 737 738 739 740 741 742 743 744 745 746 747 748 749 750 751 752

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 753 754 755 756 757 758 759 760 761 762 763 764 765 766 767 768

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 769 770 771 772 773 774 775 776 777 778 779 780 781 782 783 784

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 785 786 787 788 789 790 791 792 793 794 795 796 797 798 799 800

#> 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 801 802 803 804 805 806 807 808 809 810 811 812 813 814 815 816

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 817 818 819 820 821 822 823 824 825 826 827 828 829 830 831 832

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 833 834 835 836 837 838 839 840 841 842 843 844 845 846 847 848

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 849 850 851 852 853 854 855 856 857 858 859 860 861 862 863 864

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11

#> 865 866 867 868 869 870 871 872 873 874 875 876 877 878 879 880

#> 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11

#> 881 882 883 884 885 886 887 888 889 890 891 892 893 894 895 896

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 897 898 899 900 901 902 903 904 905 906 907 908 909 910 911 912

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 913 914 915 916 917 918 919 920 921 922 923 924 925 926 927 928

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 929 930 931 932 933 934 935 936 937 938 939 940 941 942 943 944

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 945 946 947 948 949 950 951 952 953 954 955 956 957 958 959 960

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11

#> 961 962 963 964 965 966 967 968 969 970 971 972 973 974 975 976

#> 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 977 978 979 980 981 982 983 984 985 986 987 988 989 990 991 992

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 993 994 995 996 997 998 999 1000 1001 1002 1003 1004 1005 1006 1007 1008

#> 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59

#> 1009 1010 1011 1012 1013 1014 1015 1016 1017 1018 1019 1020 1021 1022 1023 1024

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 1025 1026 1027 1028 1029 1030 1031 1032 1033 1034 1035 1036 1037 1038 1039 1040

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59

#> 1041 1042 1043 1044 1045 1046 1047 1048 1049 1050 1051 1052 1053 1054 1055 1056

#> 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11

#> 1057 1058 1059 1060 1061 1062 1063 1064 1065 1066 1067 1068 1069 1070 1071 1072

#> 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 1073 1074 1075 1076 1077 1078 1079 1080 1081 1082 1083 1084 1085 1086 1087 1088

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11

#> 1089 1090 1091 1092 1093 1094 1095 1096 1097 1098 1099 1100 1101 1102 1103 1104

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1105 1106 1107 1108 1109 1110 1111 1112 1113 1114 1115 1116 1117 1118 1119 1120

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1121 1122 1123 1124 1125 1126 1127 1128 1129 1130 1131 1132 1133 1134 1135 1136

#> 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1137 1138 1139 1140 1141 1142 1143 1144 1145 1146 1147 1148 1149 1150 1151 1152

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59

#> 1153 1154 1155 1156 1157 1158 1159 1160 1161 1162 1163 1164 1165 1166 1167 1168

#> 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1169 1170 1171 1172 1173 1174 1175 1176 1177 1178 1179 1180 1181 1182 1183 1184

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11

#> 1185 1186 1187 1188 1189 1190 1191 1192 1193 1194 1195 1196 1197 1198 1199 1200

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11

#> 1201 1202 1203 1204 1205 1206 1207 1208 1209 1210 1211 1212 1213 1214 1215 1216

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1217 1218 1219 1220 1221 1222 1223 1224 1225 1226 1227 1228 1229 1230 1231 1232

#> 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59

#> 1233 1234 1235 1236 1237 1238 1239 1240 1241 1242 1243 1244 1245 1246 1247 1248

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 1249 1250 1251 1252 1253 1254 1255 1256 1257 1258 1259 1260 1261 1262 1263 1264

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11

#> 1265 1266 1267 1268 1269 1270 1271 1272 1273 1274 1275 1276 1277 1278 1279 1280

#> 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.59

#> 1281 1282 1283 1284 1285 1286 1287 1288 1289 1290 1291 1292 1293 1294 1295 1296

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11

#> 1297 1298 1299 1300 1301 1302 1303 1304 1305 1306 1307 1308 1309

#> 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11 0.59 0.59 0.11 0.11 0.11Each probability represents the expected survival chance for that passenger, according to the model. You can think about it like the chance of survival if you put that passenger on a large number of identical Titanic voyages. Out of 100 identical voyages, how many times would that passenger survive?

1.3 Convert probabilities to decisions

To turn probabilities into decisions (we’re working for an insurance agency after all), we need a decision rule. To keep things simple, we will use a cutoff of 0.5: if the predicted probability is greater than 0.5, we predict survival (1); otherwise, we predict non-survival (0).

Click for a hint

#> 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

#> 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0

#> 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32

#> 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0

#> 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48

#> 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0

#> 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64

#> 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1

#> 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80

#> 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1

#> 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96

#> 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1

#> 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112

#> 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1

#> 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128

#> 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1

#> 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144

#> 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0

#> 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160

#> 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1

#> 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176

#> 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192

#> 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0

#> 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208

#> 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1

#> 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224

#> 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0

#> 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240

#> 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256

#> 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1

#> 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272

#> 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 273 274 275 276 277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288

#> 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0

#> 289 290 291 292 293 294 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304

#> 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320

#> 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1

#> 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336

#> 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0

#> 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352

#> 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0

#> 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368

#> 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0

#> 369 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384

#> 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0

#> 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400

#> 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0

#> 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416

#> 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1

#> 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0

#> 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448

#> 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0

#> 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464

#> 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0

#> 465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480

#> 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1

#> 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490 491 492 493 494 495 496

#> 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0

#> 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504 505 506 507 508 509 510 511 512

#> 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 513 514 515 516 517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525 526 527 528

#> 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 529 530 531 532 533 534 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 542 543 544

#> 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0

#> 545 546 547 548 549 550 551 552 553 554 555 556 557 558 559 560

#> 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1

#> 561 562 563 564 565 566 567 568 569 570 571 572 573 574 575 576

#> 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1

#> 577 578 579 580 581 582 583 584 585 586 587 588 589 590 591 592

#> 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1

#> 593 594 595 596 597 598 599 600 601 602 603 604 605 606 607 608

#> 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1

#> 609 610 611 612 613 614 615 616 617 618 619 620 621 622 623 624

#> 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1

#> 625 626 627 628 629 630 631 632 633 634 635 636 637 638 639 640

#> 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0

#> 641 642 643 644 645 646 647 648 649 650 651 652 653 654 655 656

#> 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0

#> 657 658 659 660 661 662 663 664 665 666 667 668 669 670 671 672

#> 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0

#> 673 674 675 676 677 678 679 680 681 682 683 684 685 686 687 688

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1

#> 689 690 691 692 693 694 695 696 697 698 699 700 701 702 703 704

#> 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 705 706 707 708 709 710 711 712 713 714 715 716 717 718 719 720

#> 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 721 722 723 724 725 726 727 728 729 730 731 732 733 734 735 736

#> 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

#> 737 738 739 740 741 742 743 744 745 746 747 748 749 750 751 752

#> 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0

#> 753 754 755 756 757 758 759 760 761 762 763 764 765 766 767 768

#> 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0

#> 769 770 771 772 773 774 775 776 777 778 779 780 781 782 783 784

#> 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

#> 785 786 787 788 789 790 791 792 793 794 795 796 797 798 799 800

#> 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0

#> 801 802 803 804 805 806 807 808 809 810 811 812 813 814 815 816

#> 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0

#> 817 818 819 820 821 822 823 824 825 826 827 828 829 830 831 832

#> 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0

#> 833 834 835 836 837 838 839 840 841 842 843 844 845 846 847 848

#> 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0

#> 849 850 851 852 853 854 855 856 857 858 859 860 861 862 863 864

#> 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0

#> 865 866 867 868 869 870 871 872 873 874 875 876 877 878 879 880

#> 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0

#> 881 882 883 884 885 886 887 888 889 890 891 892 893 894 895 896

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

#> 897 898 899 900 901 902 903 904 905 906 907 908 909 910 911 912

#> 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0

#> 913 914 915 916 917 918 919 920 921 922 923 924 925 926 927 928

#> 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0

#> 929 930 931 932 933 934 935 936 937 938 939 940 941 942 943 944

#> 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1

#> 945 946 947 948 949 950 951 952 953 954 955 956 957 958 959 960

#> 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0

#> 961 962 963 964 965 966 967 968 969 970 971 972 973 974 975 976

#> 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1

#> 977 978 979 980 981 982 983 984 985 986 987 988 989 990 991 992

#> 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0

#> 993 994 995 996 997 998 999 1000 1001 1002 1003 1004 1005 1006 1007 1008

#> 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1

#> 1009 1010 1011 1012 1013 1014 1015 1016 1017 1018 1019 1020 1021 1022 1023 1024

#> 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

#> 1025 1026 1027 1028 1029 1030 1031 1032 1033 1034 1035 1036 1037 1038 1039 1040

#> 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1

#> 1041 1042 1043 1044 1045 1046 1047 1048 1049 1050 1051 1052 1053 1054 1055 1056

#> 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0

#> 1057 1058 1059 1060 1061 1062 1063 1064 1065 1066 1067 1068 1069 1070 1071 1072

#> 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1

#> 1073 1074 1075 1076 1077 1078 1079 1080 1081 1082 1083 1084 1085 1086 1087 1088

#> 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 1089 1090 1091 1092 1093 1094 1095 1096 1097 1098 1099 1100 1101 1102 1103 1104

#> 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

#> 1105 1106 1107 1108 1109 1110 1111 1112 1113 1114 1115 1116 1117 1118 1119 1120

#> 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 1121 1122 1123 1124 1125 1126 1127 1128 1129 1130 1131 1132 1133 1134 1135 1136

#> 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0

#> 1137 1138 1139 1140 1141 1142 1143 1144 1145 1146 1147 1148 1149 1150 1151 1152

#> 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1

#> 1153 1154 1155 1156 1157 1158 1159 1160 1161 1162 1163 1164 1165 1166 1167 1168

#> 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 1169 1170 1171 1172 1173 1174 1175 1176 1177 1178 1179 1180 1181 1182 1183 1184

#> 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0

#> 1185 1186 1187 1188 1189 1190 1191 1192 1193 1194 1195 1196 1197 1198 1199 1200

#> 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 1201 1202 1203 1204 1205 1206 1207 1208 1209 1210 1211 1212 1213 1214 1215 1216

#> 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0

#> 1217 1218 1219 1220 1221 1222 1223 1224 1225 1226 1227 1228 1229 1230 1231 1232

#> 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1

#> 1233 1234 1235 1236 1237 1238 1239 1240 1241 1242 1243 1244 1245 1246 1247 1248

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1

#> 1249 1250 1251 1252 1253 1254 1255 1256 1257 1258 1259 1260 1261 1262 1263 1264

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0

#> 1265 1266 1267 1268 1269 1270 1271 1272 1273 1274 1275 1276 1277 1278 1279 1280

#> 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1

#> 1281 1282 1283 1284 1285 1286 1287 1288 1289 1290 1291 1292 1293 1294 1295 1296

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0

#> 1297 1298 1299 1300 1301 1302 1303 1304 1305 1306 1307 1308 1309

#> 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0Click for a solution

yhat_apparent <- ifelse(p_apparent > 0.5, 1, 0)

yhat_apparent

#> 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

#> 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0

#> 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32

#> 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0

#> 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48

#> 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0

#> 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64

#> 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1

#> 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80

#> 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1

#> 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96

#> 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1

#> 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112

#> 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1

#> 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128

#> 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1

#> 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144

#> 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0

#> 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160

#> 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1

#> 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176

#> 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192

#> 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0

#> 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208

#> 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1

#> 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224

#> 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0

#> 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240

#> 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256

#> 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1

#> 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272

#> 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 273 274 275 276 277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288

#> 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0

#> 289 290 291 292 293 294 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304

#> 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320

#> 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1

#> 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336

#> 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0

#> 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352

#> 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0

#> 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368

#> 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0

#> 369 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384

#> 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0

#> 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400

#> 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0

#> 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416

#> 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1

#> 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0

#> 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448

#> 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0

#> 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464

#> 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0

#> 465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480

#> 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1

#> 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490 491 492 493 494 495 496

#> 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0

#> 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504 505 506 507 508 509 510 511 512

#> 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 513 514 515 516 517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525 526 527 528

#> 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 529 530 531 532 533 534 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 542 543 544

#> 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0

#> 545 546 547 548 549 550 551 552 553 554 555 556 557 558 559 560

#> 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1

#> 561 562 563 564 565 566 567 568 569 570 571 572 573 574 575 576

#> 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1

#> 577 578 579 580 581 582 583 584 585 586 587 588 589 590 591 592

#> 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1

#> 593 594 595 596 597 598 599 600 601 602 603 604 605 606 607 608

#> 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1

#> 609 610 611 612 613 614 615 616 617 618 619 620 621 622 623 624

#> 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1

#> 625 626 627 628 629 630 631 632 633 634 635 636 637 638 639 640

#> 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0

#> 641 642 643 644 645 646 647 648 649 650 651 652 653 654 655 656

#> 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0

#> 657 658 659 660 661 662 663 664 665 666 667 668 669 670 671 672

#> 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0

#> 673 674 675 676 677 678 679 680 681 682 683 684 685 686 687 688

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1

#> 689 690 691 692 693 694 695 696 697 698 699 700 701 702 703 704

#> 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 705 706 707 708 709 710 711 712 713 714 715 716 717 718 719 720

#> 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 721 722 723 724 725 726 727 728 729 730 731 732 733 734 735 736

#> 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

#> 737 738 739 740 741 742 743 744 745 746 747 748 749 750 751 752

#> 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0

#> 753 754 755 756 757 758 759 760 761 762 763 764 765 766 767 768

#> 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0

#> 769 770 771 772 773 774 775 776 777 778 779 780 781 782 783 784

#> 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

#> 785 786 787 788 789 790 791 792 793 794 795 796 797 798 799 800

#> 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0

#> 801 802 803 804 805 806 807 808 809 810 811 812 813 814 815 816

#> 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0

#> 817 818 819 820 821 822 823 824 825 826 827 828 829 830 831 832

#> 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0

#> 833 834 835 836 837 838 839 840 841 842 843 844 845 846 847 848

#> 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0

#> 849 850 851 852 853 854 855 856 857 858 859 860 861 862 863 864

#> 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0

#> 865 866 867 868 869 870 871 872 873 874 875 876 877 878 879 880

#> 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0

#> 881 882 883 884 885 886 887 888 889 890 891 892 893 894 895 896

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

#> 897 898 899 900 901 902 903 904 905 906 907 908 909 910 911 912

#> 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0

#> 913 914 915 916 917 918 919 920 921 922 923 924 925 926 927 928

#> 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0

#> 929 930 931 932 933 934 935 936 937 938 939 940 941 942 943 944

#> 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1

#> 945 946 947 948 949 950 951 952 953 954 955 956 957 958 959 960

#> 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0

#> 961 962 963 964 965 966 967 968 969 970 971 972 973 974 975 976

#> 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1

#> 977 978 979 980 981 982 983 984 985 986 987 988 989 990 991 992

#> 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0

#> 993 994 995 996 997 998 999 1000 1001 1002 1003 1004 1005 1006 1007 1008

#> 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1

#> 1009 1010 1011 1012 1013 1014 1015 1016 1017 1018 1019 1020 1021 1022 1023 1024

#> 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

#> 1025 1026 1027 1028 1029 1030 1031 1032 1033 1034 1035 1036 1037 1038 1039 1040

#> 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1

#> 1041 1042 1043 1044 1045 1046 1047 1048 1049 1050 1051 1052 1053 1054 1055 1056

#> 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0

#> 1057 1058 1059 1060 1061 1062 1063 1064 1065 1066 1067 1068 1069 1070 1071 1072

#> 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1

#> 1073 1074 1075 1076 1077 1078 1079 1080 1081 1082 1083 1084 1085 1086 1087 1088

#> 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 1089 1090 1091 1092 1093 1094 1095 1096 1097 1098 1099 1100 1101 1102 1103 1104

#> 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

#> 1105 1106 1107 1108 1109 1110 1111 1112 1113 1114 1115 1116 1117 1118 1119 1120

#> 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 1121 1122 1123 1124 1125 1126 1127 1128 1129 1130 1131 1132 1133 1134 1135 1136

#> 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0

#> 1137 1138 1139 1140 1141 1142 1143 1144 1145 1146 1147 1148 1149 1150 1151 1152

#> 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1

#> 1153 1154 1155 1156 1157 1158 1159 1160 1161 1162 1163 1164 1165 1166 1167 1168

#> 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> 1169 1170 1171 1172 1173 1174 1175 1176 1177 1178 1179 1180 1181 1182 1183 1184

#> 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0

#> 1185 1186 1187 1188 1189 1190 1191 1192 1193 1194 1195 1196 1197 1198 1199 1200

#> 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 1201 1202 1203 1204 1205 1206 1207 1208 1209 1210 1211 1212 1213 1214 1215 1216

#> 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0

#> 1217 1218 1219 1220 1221 1222 1223 1224 1225 1226 1227 1228 1229 1230 1231 1232

#> 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1

#> 1233 1234 1235 1236 1237 1238 1239 1240 1241 1242 1243 1244 1245 1246 1247 1248

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1

#> 1249 1250 1251 1252 1253 1254 1255 1256 1257 1258 1259 1260 1261 1262 1263 1264

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0

#> 1265 1266 1267 1268 1269 1270 1271 1272 1273 1274 1275 1276 1277 1278 1279 1280

#> 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1

#> 1281 1282 1283 1284 1285 1286 1287 1288 1289 1290 1291 1292 1293 1294 1295 1296

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0

#> 1297 1298 1299 1300 1301 1302 1303 1304 1305 1306 1307 1308 1309

#> 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 01.4 Compute apparent accuracy

Now, we can compute the model’s accuracy. Here we are defining accuracy as the proportion of correct predictions (both survivors and non-survivors) out of all passengers.

1.3. Compute the model’s accuracy. We define accuracy as the proportion of correct predictions (both survivors and non-survivors) out of all passengers.

Click for a hint

#> [1] 0.78Click for a solution

You should get an accuracy of around 0.78, which looks pretty good at first glance. But remember, this is the model’s performance on data it has already seen. It is not a measure of how well the model would perform on new, unseen passengers.

At this point, the model looks fairly good. In fact, the number looks reassuring. But it answers the wrong question. The model is being evaluated on passengers it already “knows.” This is like asking, after the Titanic sank, whether you can explain who survived. Of course you can…

Based on these data we correctly predict 78% of the passengers. But that doesn’t tell us how well the model would have predicted survival for passengers before the disaster. Cross validation exists because this number tells us very little about how well the model would perform before the disaster. Real predictions are made before the ship hits the iceberg.

1.5 Reflection

- Why is apparent accuracy likely to be an overestimate of true predictive performance?

- Can you think of an analogy from everyday life where “testing on the same data you trained on” would give misleadingly good results?

Part 2: Holding passengers back

To get a more honest answer, we need to pretend that some passengers are unknown.

We’ll do this by splitting the data into two groups: - a training set, used to fit the model - a test set, used only for evaluation

This is the simplest form of honest evaluation. The model never sees the test data during training, so its performance on that set can’t over capitalize on chance.

Conveniently, the titanic package already provides such a split.

titanic_test %>% glimpse()

#> Rows: 418

#> Columns: 12

#> $ passengerid <int> 892, 893, 894, 895, 896, 897, 898, 899, 900, 901, 902, 903…

#> $ pclass <int> 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3…

#> $ name <chr> "Kelly, Mr. James", "Wilkes, Mrs. James (Ellen Needs)", "M…

#> $ sex <chr> "male", "female", "male", "male", "female", "male", "femal…

#> $ age <dbl> 34, 47, 62, 27, 22, 14, 30, 26, 18, 21, NA, 46, 23, 63, 47…

#> $ sibsp <int> 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 2, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0…

#> $ parch <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0…

#> $ ticket <chr> "330911", "363272", "240276", "315154", "3101298", "7538",…

#> $ fare <dbl> 7.8, 7.0, 9.7, 8.7, 12.3, 9.2, 7.6, 29.0, 7.2, 24.1, 7.9, …

#> $ cabin <chr> "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "B45", "",…

#> $ embarked <chr> "Q", "S", "Q", "S", "S", "S", "Q", "S", "C", "S", "S", "S"…

#> $ pclass_ord <ord> 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3…Exercise 2: Train/test split

2.1. Fit the same model as before (survived ~ sex + pclass), but only on the training data. Save it as m_split.

Click for a hint

#>

#> Call:

#> glm(formula = survived ~ sex + pclass, family = binomial, data = titanic_train)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) 3.295 0.297 11.08 <2e-16

#> sexmale -2.643 0.184 -14.38 <2e-16

#> pclass -0.961 0.106 -9.06 <2e-16

#>

#> (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

#>

#> Null deviance: 1186.7 on 890 degrees of freedom

#> Residual deviance: 827.2 on 888 degrees of freedom

#> AIC: 833.2

#>

#> Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4Click for a solution

m_split <- glm(

survived ~ sex + pclass,

data = titanic_train,

family = binomial

)

summary(m_split)

#>

#> Call:

#> glm(formula = survived ~ sex + pclass, family = binomial, data = titanic_train)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) 3.295 0.297 11.08 <2e-16

#> sexmale -2.643 0.184 -14.38 <2e-16

#> pclass -0.961 0.106 -9.06 <2e-16

#>

#> (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

#>

#> Null deviance: 1186.7 on 890 degrees of freedom

#> Residual deviance: 827.2 on 888 degrees of freedom

#> AIC: 833.2

#>

#> Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 42.2 Training accuracy

Let’s compute the model’s accuracy on the data it was trained on. This is still “apparent” accuracy, but now limited to the training set.

Starter code

Click for a hint

#> [1] 0.792.3 Test accuracy

Now the real test. We evaluate this model on passengers it has never seen, using titanic_test. Notice the crucial difference: we pass newdata = titanic_test to predict(). This forces the model to make predictions for passengers that played no role in fitting its coefficients.

Starter code

Click for a hint

#> [1] NaN2.4 Reflection

- Which is larger,

acc_trainoracc_test? Why is that the typical pattern? - Which estimate is closer to what Lloyd’s actually needs — a measure of how well the model explains past data, or how well it predicts future passengers?

- If

acc_testhappened to be higher thanacc_train, would that invalidate the logic of holdout testing? Explain.

Exercise 3: Cross validation across timelines

A single split is a single alternate timeline. Maybe your held-out passengers were unusually predictable, or maybe unusually hard. Either way, a single test accuracy estimate carries uncertainty about which passengers ended up in the test set.

Cross validation reduces this dependence on a single split by repeating the train/test game across multiple partitions. Here’s the idea: instead of splitting once, we split the data into k roughly equal-sized pieces (called “folds”). We train on k - 1 folds and test on the remaining fold, then rotate until every fold has served as the test set exactly once. The result is k accuracy estimates, which we can average for a more stable overall measure.

3.1 Create folds

Create titanic_cv by:

- filtering to complete cases on

survived,sex, andpclass, - setting a seed for reproducibility,

- adding a

foldvariable with values 1 through 10, assigned randomly.

Starter code

Click for a hint

Use rep(1:10, length.out = n()) so folds are roughly equal-sized. The sample() call shuffles the fold assignments randomly.

#> # A tibble: 10 × 2

#> fold n

#> <int> <int>

#> 1 1 131

#> 2 2 131

#> 3 3 131

#> 4 4 131

#> 5 5 131

#> 6 6 131

#> 7 7 131

#> 8 8 131

#> 9 9 131

#> 10 10 130Click for a solution

set.seed(11)

titanic_cv <- titanic3 %>%

filter(!is.na(survived), !is.na(sex), !is.na(pclass)) %>%

mutate(fold = sample(rep(1:10, length.out = n())))

titanic_cv %>% count(fold)

#> # A tibble: 10 × 2

#> fold n

#> <int> <int>

#> 1 1 131

#> 2 2 131

#> 3 3 131

#> 4 4 131

#> 5 5 131

#> 6 6 131

#> 7 7 131

#> 8 8 131

#> 9 9 131

#> 10 10 1303.2 Fit and evaluate 10 models

Now the core of cross validation. Complete the loop so that each fold is used as the test set exactly once. For each iteration:

- Split the data: everything except fold

jis the training set; foldjis the test set. - Fit the logistic regression on the training set.

- Predict on the test set and compute accuracy.

Store the fold accuracies in cv_results.

Starter code

cv_results <- data.frame(fold = sort(unique(titanic_cv$fold)), accuracy = NA_real_)

for (j in cv_results$fold) {

train_j <- titanic_cv %>% filter(fold != ___)

test_j <- titanic_cv %>% filter(fold == ___)

m_j <- glm(

formula = ___,

data = ___,

family = ___

)

p_j <- predict(m_j, newdata = ___, type = ___)

yhat_j <- ifelse(___ > ___, ___, ___)

cv_results$accuracy[cv_results$fold == j] <- mean(___ == ___, na.rm = TRUE)

}Click for a hint

The key idea: filter(fold != j) gives you all rows except fold j (your training set), and filter(fold == j) gives you just fold j (your test set). The formula, family, and prediction steps are the same as in Exercises 1 and 2.

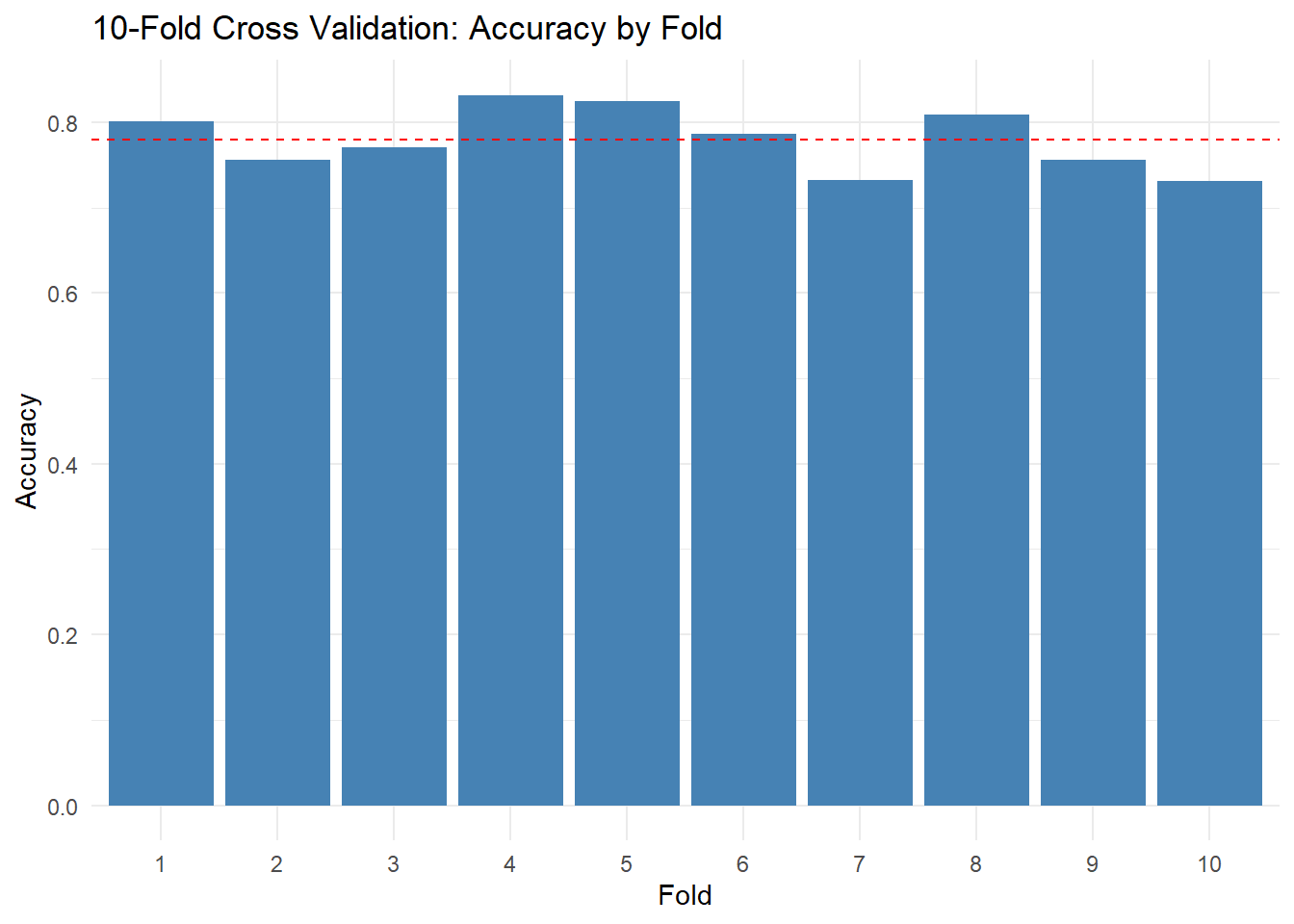

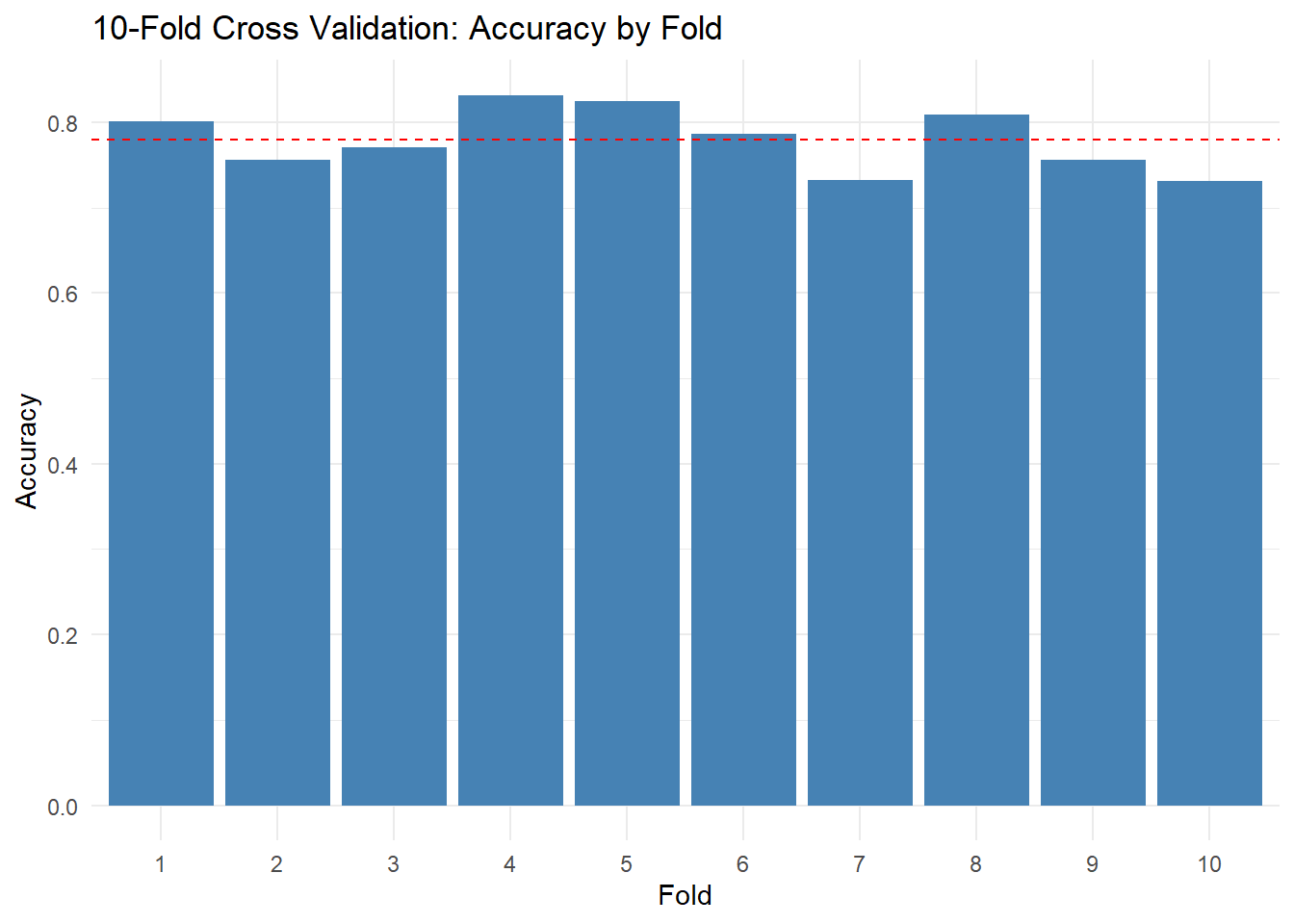

#> fold accuracy

#> 1 1 0.80

#> 2 2 0.76

#> 3 3 0.77

#> 4 4 0.83

#> 5 5 0.82

#> 6 6 0.79

#> 7 7 0.73

#> 8 8 0.81

#> 9 9 0.76

#> 10 10 0.73Click for a solution

cv_results <- data.frame(fold = sort(unique(titanic_cv$fold)), accuracy = NA_real_)

for (j in cv_results$fold) {

train_j <- titanic_cv %>% filter(fold != j)

test_j <- titanic_cv %>% filter(fold == j)

m_j <- glm(

formula = survived ~ sex + pclass,

data = train_j,

family = binomial

)

p_j <- predict(m_j, newdata = test_j, type = "response")

yhat_j <- ifelse(p_j > 0.5, 1, 0)

cv_results$accuracy[cv_results$fold == j] <- mean(yhat_j == test_j$survived, na.rm = TRUE)

}

cv_results %>% arrange(fold)

#> fold accuracy

#> 1 1 0.80

#> 2 2 0.76

#> 3 3 0.77

#> 4 4 0.83

#> 5 5 0.82

#> 6 6 0.79

#> 7 7 0.73

#> 8 8 0.81

#> 9 9 0.76

#> 10 10 0.733.3 Summarize cross validation

Now that we have 10 accuracy estimates (one per fold), we can summarize them. Compute the mean, SD, min, and max of fold accuracy.

Starter code

Click for a hint

#> cv_mean cv_sd cv_min cv_max

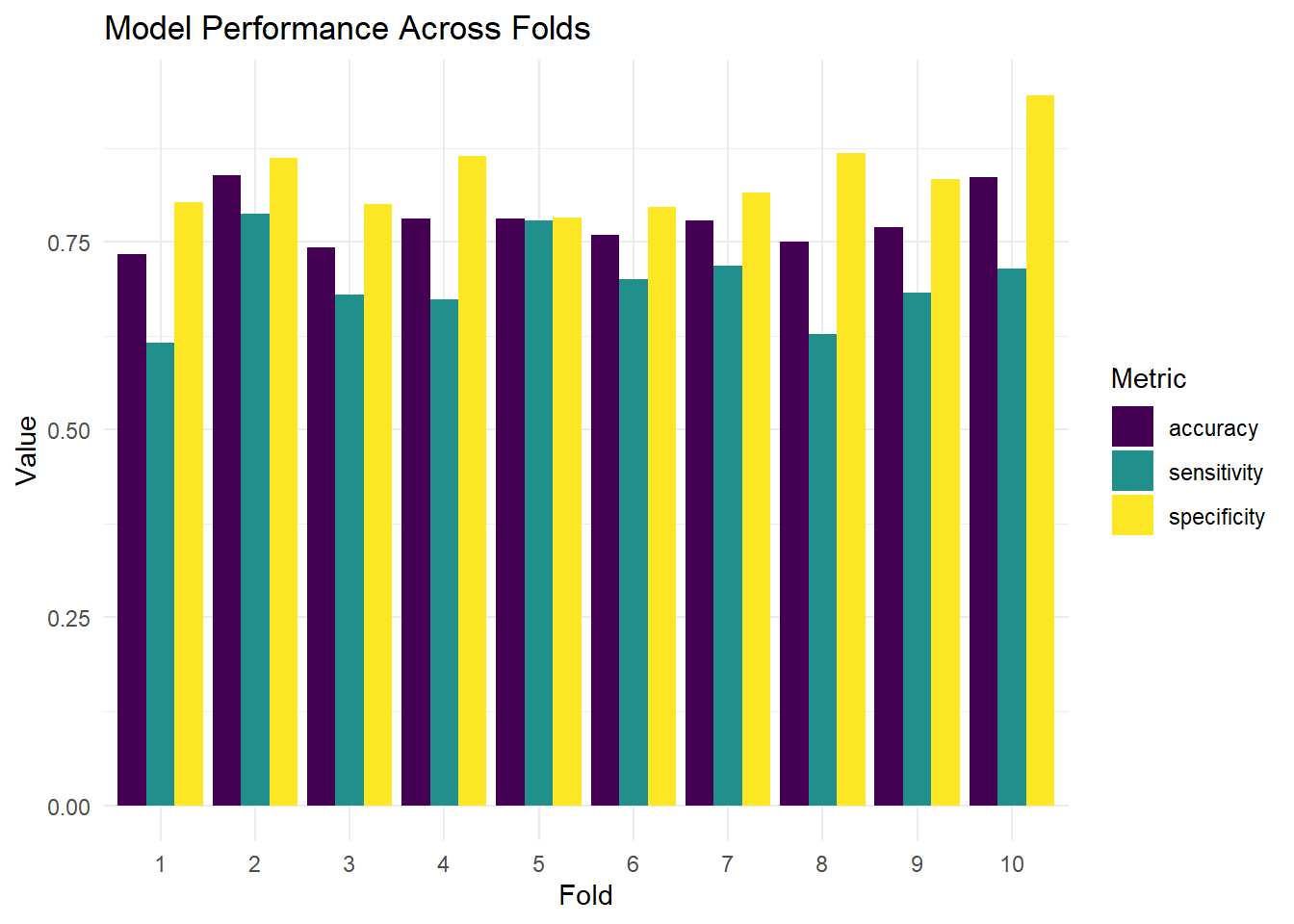

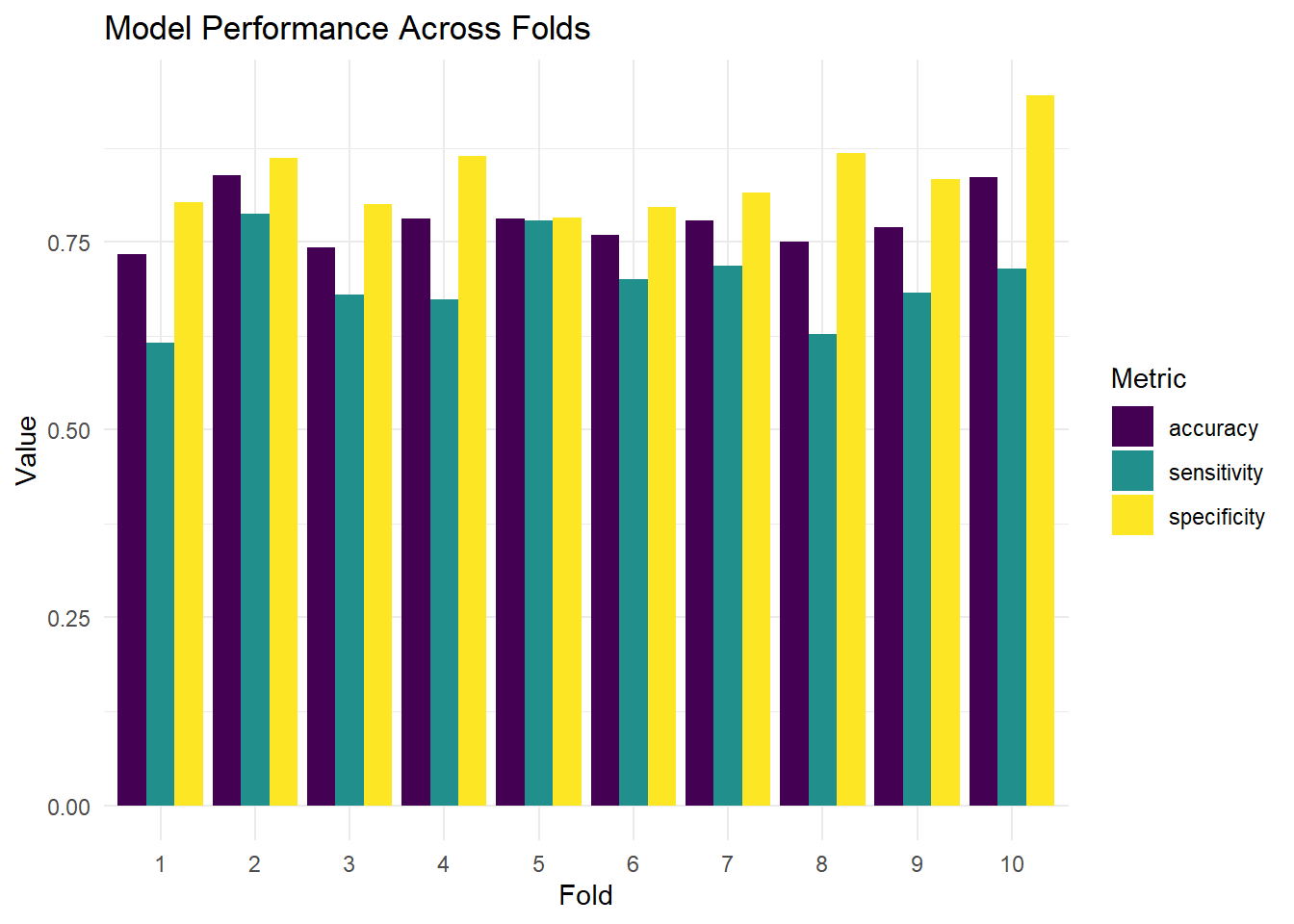

#> 0.780 0.036 0.731 0.8323.4 Visualize fold performance

It’s helpful to see how accuracy varies across folds. Create a simple bar chart or dot plot of the 10 fold accuracies. This visualization makes the variability concrete — you can see which folds were “easy” and which were “hard.”

Starter code

Click for a hint

Click for a solution

ggplot(cv_results, aes(x = factor(fold), y = accuracy)) +

geom_col(fill = "steelblue") +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(cv_results$accuracy), linetype = "dashed", color = "red") +

labs(

title = "10-Fold Cross Validation: Accuracy by Fold",

x = "Fold",

y = "Accuracy"

) +

theme_minimal()

Exercise 4: When the cutoff is a policy decision

A probability cutoff is not a law of nature. It is a decision.

Lloyd’s might treat “predict survival” as a proxy for “low risk,” but different cutoffs change what counts as low risk. A cutoff of 0.3 is generous: it labels many passengers as likely survivors, which could lead to under-pricing risk. A cutoff of 0.7 is conservative: it labels most passengers as non-survivors, which might over-price risk. The “right” cutoff depends on the costs of different errors — and those costs are a business decision, not a statistical one.

In this exercise you will examine how accuracy changes as the cutoff changes.

4.1 Evaluate multiple cutoffs on the test set

Using p_test from Exercise 2, compute test accuracy for the following cutoffs: 0.3, 0.5, 0.7.

Create a data frame called cutoff_results with columns cutoff and accuracy.

Starter code

Click for a hint

#> cutoff accuracy

#> 1 0.3 NaN

#> 2 0.5 NaN

#> 3 0.7 NaNClick for a solution

cutoffs <- c(0.3, 0.5, 0.7)

cutoff_results <- data.frame(

cutoff = cutoffs,

accuracy = NA_real_

)

for (i in seq_along(cutoffs)) {

c0 <- cutoffs[i]

yhat_c <- ifelse(p_test > c0, 1, 0)

cutoff_results$accuracy[i] <- mean(yhat_c == titanic_test$survived, na.rm = TRUE)

}

cutoff_results

#> cutoff accuracy

#> 1 0.3 NaN

#> 2 0.5 NaN

#> 3 0.7 NaN4.2 Visualize cutoff performance

To make the trade-off more concrete, let’s expand the analysis. Evaluate accuracy across a finer grid of cutoffs and plot the results. This will reveal that accuracy is not a smooth function of the cutoff — it can have a plateau or multiple peaks.

Starter code

Click for a hint

#> Warning: Removed 17 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

#> (`geom_line()`).

#> Warning: Removed 17 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

#> (`geom_point()`).

Click for a solution

cutoffs_fine <- seq(0.1, 0.9, by = 0.05)

cutoff_results_fine <- data.frame(

cutoff = cutoffs_fine,

accuracy = NA_real_

)

for (i in seq_along(cutoffs_fine)) {

c0 <- cutoffs_fine[i]

yhat_c <- ifelse(p_test > c0, 1, 0)

cutoff_results_fine$accuracy[i] <- mean(yhat_c == titanic_test$survived, na.rm = TRUE)

}

ggplot(cutoff_results_fine, aes(x = cutoff, y = accuracy)) +

geom_line() +

geom_point() +

labs(

title = "Test Accuracy Across Probability Cutoffs",

x = "Cutoff",

y = "Accuracy"

) +

theme_minimal()

#> Warning: Removed 17 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

#> (`geom_line()`).

#> Warning: Removed 17 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

#> (`geom_point()`).

4.3 Reflection

- Which cutoff maximized accuracy here?

- Why might accuracy be a poor criterion for selecting a cutoff in underwriting? Think about what happens when the costs of false positives and false negatives differ.

- Name one alternative metric you would want if false positives and false negatives had different costs. (Hint: think about sensitivity, specificity, or expected cost.)

Stretch tasks (optional)

These are optional, but they bring the lab closer to how real modeling work looks. If you found the main exercises straightforward, these will push your understanding further.

5.1 Add one more predictor and re-run CV

Pick one additional predictor from titanic3 that you think should matter (for example, age or fare).

- Fit

survived ~ sex + pclass + <your variable>. - Run 10-fold CV again.

- Compare

cv_meanandcv_sdto the baseline model.

Important: decide how you will handle missing values for your added predictor (listwise deletion is allowed here; we will treat missingness more carefully in the super stretch exercises).

Starter code

titanic_cv51 <- titanic3 %>%

filter(!is.na(___)) %>%

filter(!is.na(___)) %>%

filter(!is.na(___)) %>%

filter(!is.na(___))

set.seed(42)

titanic_cv51 <- titanic_cv51 %>%

mutate(fold = __________________ )

cv_results51 <- data.frame(fold = ___________, accuracy = ___________)

for (j in 1:10) {

train_j <- titanic_cv51 %>% filter(fold != j)

test_j <- titanic_cv51 %>% filter(fold == j)

m_j <- glm( ___________, data = ___________, family = ___________)

p_j <- predict( ___________, newdata = ___________, type = "response")

yhat_j <- ifelse( ___________ > 0.5, 1, 0)

cv_results51$accuracy[j] <- mean(yhat_j == ___________, na.rm = TRUE)

}

c(cv_mean = mean(cv_results51$accuracy), cv_sd = sd(cv_results51$accuracy))Click for a hint

You can reuse the CV loop from Exercise 3 with a new formula. Just make sure to filter out rows where your new predictor is missing before creating folds, so that every fold has the same set of variables available.

Click for a solution example

titanic_cv51 <- titanic3 %>%

filter(!is.na(survived)) %>%

filter(!is.na(sex)) %>%

filter(!is.na(pclass)) %>%

filter(!is.na(age))

set.seed(42)

titanic_cv51 <- titanic_cv51 %>%

mutate(fold = sample(rep(1:10, length.out = n())))

cv_results51 <- data.frame(fold = 1:10, accuracy = NA_real_)

for (j in 1:10) {

train_j <- titanic_cv51 %>% filter(fold != j)

test_j <- titanic_cv51 %>% filter(fold == j)

m_j <- glm(survived ~ sex + pclass + age, data = train_j, family = binomial)

p_j <- predict(m_j, newdata = test_j, type = "response")

yhat_j <- ifelse(p_j > 0.5, 1, 0)

cv_results51$accuracy[j] <- mean(yhat_j == test_j$survived, na.rm = TRUE)

}

c(cv_mean = mean(cv_results51$accuracy), cv_sd = sd(cv_results51$accuracy))

#> cv_mean cv_sd

#> 0.781 0.0215.2 Competing models

Fit and compare at least two models using CV:

- Model A:

sex + pclass - Model B:

sex + pclass + <two more predictors>

Report which model has higher cv_mean. If the difference is small, argue which one you would recommend to Lloyd’s, considering simplicity vs performance. Remember that a simpler model is easier to explain to stakeholders and less likely to overfit.

Starter code

f_A <- survived ~ sex + pclass

f_B <- survived ~ sex + pclass + ___ + ___

cv_A <- _________(cv_df, formula = ___)

cv_B <- _________(cv_df, formula = ___)

data.frame(

model = c("A: base", "B: expanded"),

cv_mean = c(mean(cv_A$accuracy), mean(cv_B$accuracy)),

cv_sd = c(sd(cv_A$accuracy), sd(cv_B$accuracy))

)Click for a hint

#> Error in `cv_glm_accuracy()`:

#> ! could not find function "cv_glm_accuracy"

#> Error in `cv_glm_accuracy()`:

#> ! could not find function "cv_glm_accuracy"

#> Error:

#> ! object 'cv_A' not foundClick for a solution example

f_A <- survived ~ sex + pclass

f_B <- survived ~ sex + pclass + age + fare

cv_A <- cv_glm_accuracy(cv_df, formula = f_A)

#> Error in `cv_glm_accuracy()`:

#> ! could not find function "cv_glm_accuracy"

cv_B <- cv_glm_accuracy(cv_df, formula = f_B)

#> Error in `cv_glm_accuracy()`:

#> ! could not find function "cv_glm_accuracy"

data.frame(

model = c("A: base", "B: expanded"),

cv_mean = c(mean(cv_A$accuracy), mean(cv_B$accuracy)),

cv_sd = c(sd(cv_A$accuracy), sd(cv_B$accuracy))

)

#> Error:

#> ! object 'cv_A' not found5.3 Stability thought experiment

Repeat 10-fold CV but change the seed (try three different seeds). Does cv_mean change much? Does cv_sd change much?

Write 3 to 5 sentences interpreting what you see. If the results change a lot across seeds, what does that tell you about the reliability of your 10-fold estimate?

Super Stretch goals

Lloyd’s Actually Has to Use This Model

In the previous exercises, we evaluated a simple Titanic model using holdout testing and k-fold cross validation. That section began with a deliberately constrained model (sex and pclass) so you could focus on evaluation without getting lost in feature engineering.

Now we do the part Lloyd’s actually cares about: building a model that uses more information, and doing so in a way that does not quietly sabotage evaluation.

This section is about the uncomfortable truth that modeling choices are evaluation choices:

- If you add predictors with missing data, you change the population your model is trained and tested on.

- If you impute missing values using the full dataset, you leak information across folds.

- If you select a cutoff to maximize accuracy, you are making a policy decision without naming it.

You will build richer models, compare them using cross validation, and then stress-test the evaluation pipeline itself.

Additional Learning goals

- Compare multiple candidate models using k-fold cross validation.

- Handle missing data with listwise deletion and simple imputation.

- Avoid information leakage by imputing within folds.

- Evaluate classifiers beyond accuracy (confusion matrices, sensitivity/specificity).

- Reason about performance vs stability when recommending a model.

Exercise 6: Candidate models

Lloyd’s will not price risk using only sex and class. Your job is to propose reasonable candidate models and compare them using the same evaluation method. Think about what information an insurer would realistically have about a passenger before the voyage.

6.1 Choose candidate predictors

Pick two additional predictors from the data set. (This can include a constructed variable that you create from existing variables.)

names(titanic3)

#> [1] "pclass" "survived" "name" "sex" "age"

#> [6] "sibsp" "parch" "ticket" "fare" "cabin"

#> [11] "embarked" "boat" "body" "home.dest" "pclass_ord"Why do you think each predictor you selected should matter for survival? Write a brief justification for each (2-3 sentences).

Click for a hint about feature engineering

Titles extracted from names (e.g., “Mr”, “Mrs”, “Miss”, “Master”) can be powerful predictors because they encode both sex and social status. Here’s how to extract them:

Click for a sample answer

Good candidate predictors include:

age: Children were prioritized during evacuation (“women and children first”), so younger passengers likely had higher survival rates. Age also correlates with physical ability to reach lifeboats.fare: Fare is a proxy for wealth and cabin location. Higher fares corresponded to upper-deck cabins closer to the lifeboats, giving wealthier passengers a structural advantage in evacuation.embarked: Port of embarkation (Cherbourg, Queenstown, Southampton) correlates with passenger demographics and class composition, which in turn predicts survival.

Exercise 7: Cross validation comparison (listwise deletion)

We will start with the simplest missing-data strategy: drop rows with missing values in any variable used by the model.

This is not always the best approach, but it is transparent and ensures that every row in the analysis has complete information. The cost is that we may lose a substantial number of passengers.

7.1 Create a CV dataset for both models

Create cv_df that keeps only rows with non-missing values for all variables needed in f_expanded. This way, both the baseline and expanded models are evaluated on the same set of passengers — an apples-to-apples comparison.

Click for a hint

7.3 Write a function to compute CV accuracy

In the main exercises, you wrote a for loop to perform cross validation. Now let’s wrap that logic into a reusable function. This is good programming practice: once you have code that works, encapsulating it in a function makes it easier to apply repeatedly and reduces the chance of copy-paste errors.

Complete the function below so it returns a data frame with fold accuracies for a given formula.

cv_glm_accuracy <- function(df, formula, cutoff = 0.5) {

out <- data.frame(fold = sort(unique(df$fold)), accuracy = NA_real_)

for (j in out$fold) {

train_j <- df %>% filter(fold != ___)

test_j <- df %>% filter(fold == ___)

m_j <- glm(

formula = ___,

data = ___,

family = ___

)

p_j <- predict(m_j, newdata = ___, type = ___)

yhat_j <- ifelse(___ > ___, ___, ___)

out$accuracy[out$fold == j] <- mean(___ == ___, na.rm = TRUE)

}

out

}Click for a hint

This function takes a data frame df with a fold variable, a model formula, and an optional cutoff. It loops through each fold, fits the specified logistic regression model on the training set, predicts on the test set, and computes accuracy based on the cutoff. The result is a data frame with fold-wise accuracies that can be summarized or compared across models.

Click for a solution

cv_glm_accuracy <- function(df, formula, cutoff = 0.5) {

out <- data.frame(fold = sort(unique(df$fold)), accuracy = NA_real_)

for (j in out$fold) {

train_j <- df %>% filter(fold != j)

test_j <- df %>% filter(fold == j)

m_j <- glm(

formula = formula,

data = train_j,

family = binomial

)

p_j <- predict(m_j, newdata = test_j, type = "response")

yhat_j <- ifelse(p_j > cutoff, 1, 0)

out$accuracy[out$fold == j] <- mean(yhat_j == test_j$survived, na.rm = TRUE)

}

out

}7.4 Compare models

Use cv_glm_accuracy() to compute CV results for both formulas. Compute mean and SD of accuracy for each.

Starter code

Click for a hint

#> model mean_acc sd_acc

#> 1 base 0.78 0.039

#> 2 expanded 0.78 0.036Click for a solution

cv_base <- cv_glm_accuracy(cv_df, formula = f_base)

cv_exp <- cv_glm_accuracy(cv_df, formula = f_expanded)

summary_table <- data.frame(

model = c("base", "expanded"),

mean_acc = c(mean(cv_base$accuracy), mean(cv_exp$accuracy)),

sd_acc = c(sd(cv_base$accuracy), sd(cv_exp$accuracy))

)

summary_table

#> model mean_acc sd_acc

#> 1 base 0.78 0.039

#> 2 expanded 0.78 0.0367.5 Reflection

- Which model has higher mean CV accuracy?

- Which model has higher variability across folds?

- If the accuracy improvement is small but the expanded model is more variable, how would you advise Lloyd’s? Consider the trade-off between a slight improvement in average performance and greater uncertainty about how the model will perform on any given new passenger.